Indonesian Elections 2024, Asia Thinkers discuss the candidates’ foreign and domestic policy proposals and the impact of using religion to mobilise voters and win elections.

Indonesia is Southeast Asia’s growing superpower, already home to the largest economy in Southeast Asia, the tenth-largest in the world and the fourth most populous nation with over 270 million inhabitants of which over 200 million are Muslim. Indonesia will soon elect a president to succeed, Joko “Jokowi” Widodo, whose focus on economic growth has guided Indonesian foreign policy. A three-way race will decide who replaces the popular 10-year incumbent president who is ineligible to be re-elected. Any changes in either domestic or foreign policy driven by identity politics could reverberate throughout Southeast Asia. Asia Thinkers discusses with Indonesian-based political risk analysts to identify candidates’ policies, political support and the outcome of the 2024 presidential elections which are scheduled to be held in Indonesia on 14 February 2024 to elect the President and Vice President, who will be sworn in on 20 October 2024.

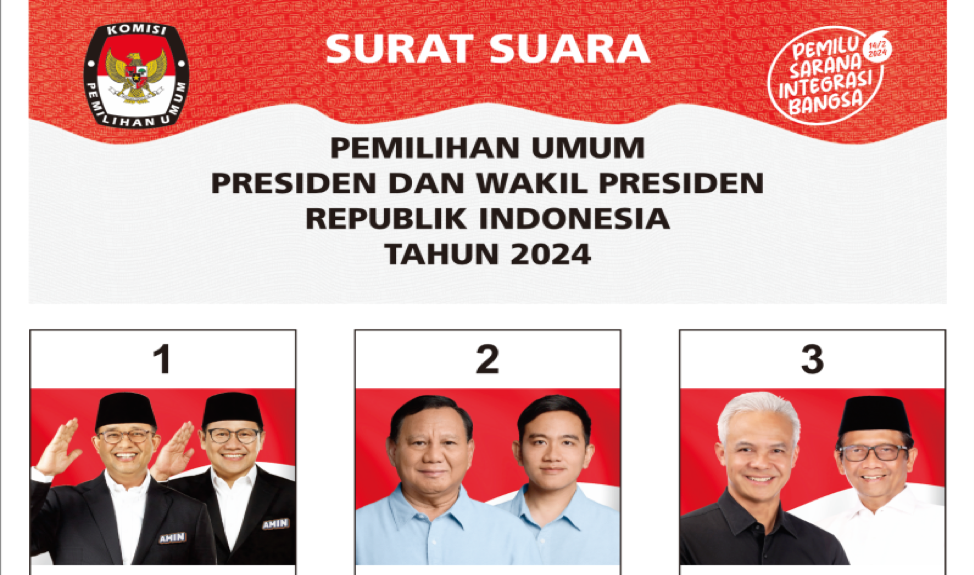

(Anies-Muhaimin (Prabowo-Gibran) (Ganjar-Mahfud))

Three pairs of presidential and vice presidential candidates are set to contest the upcoming election, scheduled on 14 February 2024. The pairs represent three political party coalitions with different policy plans and is a three-way race among ex-special forces commander and Jokowi’s two-time election opponent-turned-Defense Minister Prabowo Subianto, former Central Java Governor Ganjar Pranowo and former Jakarta Governor Anies Baswedan. While the candidate pairs Prabowo and Gibran and Ganjar-Mahfud) have been firm in their intention to carry on President Joko Widodo’s key programs, including the mega development project of the new Nusantara Capital City and the downstream of the mining sector, the pair Anies-Muhaimin have portrayed themselves as a progressive change to the Widodo administration. While there are some differences among the candidates regarding their approach to infrastructure projects, investment priorities, foreign policy direction, and strategies for energy transition, the overall policy platforms of the three candidates carry similar values of populism that broadly appeal to voters.

Presidential candidates Anies Baswedan, Prabowo Subianto, and Ganjar Pranowo, Getty Images

Key policy promises

Prabowo and Ganjar have laid out relatively similar economic policies, with both pledging to retain President Widodo’s downstream industrial policy, particularly in the mining and oil and gas sectors. Meanwhile, Anies’ economic pledges have centred around creating a just and prosperous society for all. In terms of infrastructure, both Prabowo and Ganjar have also pledged to finish Widodo’s plans for the development of the Nusantara Capital City in Kalimantan, while Anies has not mentioned the mega project in his vision and mission manifesto.

All candidates are focusing on economic growth, job creation, the cutting of national debt, and the reduction of poverty — although the targets and methodology vary. All manifestos indicated commitments to addressing climate change and deforestation including the reduction in greenhouse gas emissions through the early retirement of coal-fired power plants, and instead increasing renewable energy development in the country. The candidates have emphasised the green and blue (ocean) economies as potential solutions. Each candidate has varying degrees of commitment when balancing economic objectives.

Candidates’ views on Foreign Policy

The current economic-driven foreign policy is not expected to change significantly under either Ganjar or Prabowo, as both candidates have expressed a desire to build closer ties with China, Indonesia’s largest trading partner. A trade and investment-driven approach to foreign policy may mean increased engagement and closer ties with China as well as with other trading partners, such as the United Arab Emirates and other Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries.

The Anies-Muhaimin foreign policy platform emphasises positioning Indonesia as “a balancing force in the global order,” so that the country can “prevent the domination of certain powers”. Anies recently said that Indonesia needs to continue its non-alignment approach but should aim to be proactive in the international arena. He has several times declared his intention to adopt a “values-based” foreign policy. This is one in which a country has a clear stance and upholds it, where other concerns other than investment and trade, take priority. If elected, Indonesia would take on a bigger role in the United Nations peacekeeping force and also as a “mediator” for world peace, including for Palestine. Anies-Muhaimin’s foreign policy program mentions ASEAN and Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) among several regional institutions he will deepen engagement with under his administration.

The Prabowo-Gibran pair, on the other hand, stated that they would seek to improve Indonesia’s international standing by strengthening maritime diplomacy and actively pushing Indonesia to open an embassy in Palestine. Prabowo has indicated that he is open to Indonesia joining BRICS, an informal grouping comprising Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa. In 2023, Indonesia declined an invitation to join BRICS due to concerns that Indonesia might be seen as sympathising with China and Russia’s efforts to challenge the United States’ leadership of the international order. Meanwhile, Ganjar’s foreign policy proposal has many similarities to President Widodo’s policies. Most notably, it is focused on five areas; Indonesia as a centre for global rice production; energy security, including electricity exports, securing Indonesia’s maritime borders, industrial “downstreaming” and protecting Indonesian citizens overseas. However, his foreign policy manifesto does not mention the United Nations, despite Indonesia’s contributions as a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council and UN Peacekeeping Missions over the past six and a half decades. Ganjar’s manifesto also did not mention Indonesia’s future role in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), despite Indonesia’s enormous contributions to ASEAN governance. If elected, Ganjar is likely to delegate many foreign policy issues to the Foreign Affairs Ministry, given his lack of experience.

Many political commentators believe the most likely scenario following the election is recalibration. The next Indonesian president may not depart too far from Jokowi’s foreign policy vision but adjust the approach in some areas. This could include more scrutiny of Chinese investment into the country and a greater focus on drawing capital from other sources including Europe, Japan and the United States. This could also mean intensification in the policing of Indonesia’s boundaries, which may affect the country’s key relationships with not only China but also its neighbours such as Malaysia and Singapore.

Major powers could also be dealing with a country which is outspoken on international developments such as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the crisis in Palestine or regional issues such as China’s build-up in the South China Sea. Meanwhile exerting its influence in international forums such as the United Nations General Assembly. While on the other hand, some see no significant change to the status quo. This scenario would mean a continuation of Jokowi’s domestic-centred and economic-focused foreign policy with the country primarily focused on advancing its own goal to become one of the world’s top five economies by 2045. The focus would remain on various Industrial sectors as the country captures more value from its raw materials within the country. The construction of the new capital would continue along with energy transition initiatives. A priority would be placed on enhancing Indonesia’s sovereignty as an archipelagic state, including the curbing of illegal fishing, which involves several of the country’s neighbours.

A more radical view could see a more authoritarian approach from political leaders with support from extremist forms of Islam to shape a more ideological approach to foreign policy. This could include hostile relations with countries not seen to share Indonesia’s values and closer alignment with authoritarian countries like China, Russia and other Islamic countries. This may seem unlikely, but the influence of Islamic extremist ideology (identity politics) on candidates cannot be dismissed.

Islamic group’s influence on the elections

Religious diversity in Indonesia is often cited as a source of strength as well as a potential trigger of conflict. Indonesia is home to the world’s largest Muslim population of over 200 million out of the 270 million population, but it also has significant Christian, Hindu, Buddhist, and Confucian communities, among others. While the Indonesian 1945 Constitution guarantees freedom of religion, religious discrimination and conflict have occurred in the country’s history, including during elections over the past 10 years. There have been concerns that political candidates have sought to use religion to mobilise voters to win the 2024 elections. This has led to fears of increased tensions between religious communities.

One commentator told Asia Thinkers that “all presidential candidates have made efforts to secure the support of influential Islamic clerics and notable scholars. All three candidates have visited Islamic boarding schools and met Islamic scholars to try to secure votes from devout Muslims. Indonesia is a secular democratic country that has a Muslim-majority population, and those seeking regional to national leadership commonly attempt to gain the votes of Muslim people and avoid moves that could risk angering them.”

Ahead of the 2024 election, there is a possibility that electoral candidates might use identity politics as a strategy, regardless of the controversies attached to it. In Indonesia, the use of religious ideology for contestation in general elections has been chiefly carried out through social media as a new way of campaigning in digital public spaces. Examples of this were seen in the 2019 Presidential election which was marked by issues of religious identity being raised to influence public opinion and boost the electability of candidate pairs, rather than issues of ethnicity. In 2019 Joko Widodo, an incumbent candidate, was widely accused of being an anti-Islam figure who also supported the banned Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) and favouring foreign interests over the majority of Muslims in Indonesia. On the other hand, he went on to win the election against Prabowo Subianto who was the choice of the ultra-conservative clergy.

In the 2024 election, Anies Baswedan has become the preferred presidential candidate of hard-line Islamic groups that claim to represent Islamist populists. Notably, he is supported by two out of six Islam-based parties: the National Awakening Party (PKB) and the Prosperous Justice Party (PKS). PKS has played an effective role in opposition, fighting its battles in the pro-Widodo parliament over the past 10 years. The party is believed to have an agenda to work within the political system to turn Indonesia into an Islamic state.

Anis support includes clerics who are influential figures amongst hard-line groups, such as Rizieq Shihab who had been imprisoned for spreading fake news and has, in the past, politicised religious sentiment and Abdul Somad who supports Anies in bringing changes to the current path of Indonesia’s development and prioritising justice in policymaking. Somad considers suicide bombing to be permissible in the Israel-Palestinian conflict and believes in the martyrdom of Palestinians who carry out such attacks. Both are influential Islamic figures who have the potential to mobilise Muslim voters, as well as exploit religious sentiment in favour of Anies and Muhaimin.

Prabowo-Gibran

Although Prabowo secured the support of hardline Islamic groups in the 2019 presidential election, these groups have turned their back on Prabowo ahead of the 2024 Presidential Election. Nonetheless, reports indicate that Prabowos still maintains the support of several groups of conservative Muslims who voted for him in the 2014 and 2019 presidential elections. However, ahead of the 2024 election, Prabowo seems to be distancing himself from the hard-line Islamic groups who previously supported him. None of the notable Islamic clerics and scholars supporting Prabowo ahead of the 2024 election have been associated with hard-line Islamic groups, nor have any of them indicated the potential of politicising religion to gain votes.

Ganjar-Mahfud

To date, no controversial religious figures have declared support for these candidates and they are unlikely to get much support from Islamic moderates. It appears likely that the majority of Islamist moderates will support the pair Ganjar Prabowo, who is nominated by the Indonesian Democratic Party Struggle (PDI-P), the largest Indonesian political party, which counts secular nationalists, religious minorities, and moderate Muslims as its core constituencies.

Ahead of the 2024 election, there is a possibility that electoral candidates might use identity politics as a strategy, regardless of the controversies attached to it. However, the Indonesian Survey Institute (LSI) executive director Djayadi Hanan believes that campaigning based on identity politics will not be an effective strategy for the leading presidential candidates in the 2024 General Elections. Hanan said that “all three candidates will find it more difficult to win the election if they rely on identity politics.” Hanan continued to comment that to win the election, the candidates will likely need to appeal to independent voters beyond their support base.

Islamic organisations, clerics, and activists will play a significant role during the 2024 Indonesian presidential election as their endorsements will be sought by all presidential candidates contesting the race. The fact that the outcome of the presidential election will be determined in densely populated Central and East Java provinces, where a substantial number of senior clerics and followers reside, incentivises all presidential candidates to court these groups. Given the ideological and political divisions within political parties and the fragmented nature of the other more conservative Islamic groups in Indonesia, no single candidate may be able to secure a decisive endorsement from the majority of Indonesian Muslims.

Meanwhile, recent observation indicates that hard-line Islamic groups and the moderate Islamist community seem to be using political pragmatism instead of identity politics to choose their 2024 presidential nominee. Prabowo seems to be the main beneficiary of this emerging pragmatism. Despite his ambivalence to Islamist groups after he became Minister of Defence, he is seen by many Muslim leaders and activists as a safe candidate who could easily win the election and so worth backing. It also appears there is a growing consensus that it may be better to support a presidential candidate who is considered close to Widodo and in control of the Defence Ministry, with the largest budget among other ministries, Prabowo is increasingly viewed by many Islamic groups as the candidate best placed to deliver political favours and financial resources. These pragmatic political calculations mean concerns about his past actions during Suharto’s reign are being cast aside as a historical footnote by much of Indonesia’s political and religious establishment.

Muslim support will likely be divided among the different candidates. In addition, instead of being motivated purely by ideology, the decision of Islamic groups and personalities to support particular candidates may well depend to a large degree on the willingness of the candidates to accommodate the demands of each group and its leaders, including the potential for post-victory political appointments and other forms of patronage.